Monday Morning Art: Goodbye, Johnny

August 7, 2017 by Rudy Panucci

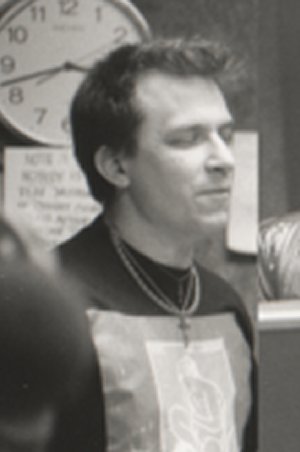

Monday Morning Art isn’t new this week. It’s a painting of Johnny Rock that I first posted here early in 2011.

Johnny Rock died Friday at the age of 49. Johnny was one of the most consequential people in my life. His death, though not unexpected, punched a hole in my heart, and I’m going to need to tell you a bit about my friend.

Johnny was larger than life, one of those people of mythic charm that you feel lucky being around. If not for Johnny, I may never have gotten involved in the local music scene to the extent that I have been for the past 28 years.

In the fall of 1989 I had just launched Radio Free Charleston on WVNS radio, and I didn’t really think that anybody was listening. I was playing a mix of alternative and progressive rock and had just started mixing in some local music that I’d come across. The show aired at 2 AM.

I was shocked when I got a call on the station line one night shortly after the show started. It was Johnny, talking to me for the first time. In his usual hurried manner of speaking, he blurted out, “Hey Rudy, love the show. I’m in a band called Go Van Gogh. We’re the best band in town and all the other bands hate us. It’d be cool if you’d come see us and play us on your show!”

I was shocked when I got a call on the station line one night shortly after the show started. It was Johnny, talking to me for the first time. In his usual hurried manner of speaking, he blurted out, “Hey Rudy, love the show. I’m in a band called Go Van Gogh. We’re the best band in town and all the other bands hate us. It’d be cool if you’d come see us and play us on your show!”

I was skeptical but curious. At that point in my life I hadn’t set foot in a bar in seven years. I lost several friends due to a drunk-driving accident and just didn’t feel comfortable in that environment. I never drank anyway, so it was no big loss.

The following Tuesday I walked into The Charleston Playhouse for the first time. It was open-mic night. The first thing I see is three-fourths of Go Van Gogh: Johnny, his brother Tim and Steve Beckner. They were playing “Rocky Raccoon” from The Beatles’ White Album. Johnny was just playing a floor tom. At that moment I was home. I needed to tell more people about this music. I had found my place in Charleston’s music scene.

I got to be good friends with Johnny and all of Go Van Gogh, and through them I met many other incredible musicians. I had Go Van Gogh on Radio Free Charleston live, where Johnny managed to accidentally drop one of the funniest f-bombs in broadcast history.

I learned that most of the people I would meet in Charleston knew Johnny from his days at Budget Tapes & Records, and even more knew him from when he worked at Hollywood Video. Johnny was a legend of Charleston’s West Side. He wouldn’t have any of that “Elk City” nonsense. It was the West Side and nothing else.

When Radio Free Charleston‘s first incarnation ended I stayed in touch with Johnny and the band. I’d go on to work with them on some video projects. I’d go out of my way to Hollywood Video to see what Johnny was recommending. It was just fun to be around Johnny, and he definitely knew his cinema.

When Radio Free Charleston‘s first incarnation ended I stayed in touch with Johnny and the band. I’d go on to work with them on some video projects. I’d go out of my way to Hollywood Video to see what Johnny was recommending. It was just fun to be around Johnny, and he definitely knew his cinema.

Go Van Gogh split up in the 1990s as the Beckner brothers moved to Nashville and the local scene hit one of its periodic doldrums. Johnny stopped playing drums, and I dropped out of most socializing to take care of my mother for more than eight years. At right you see Johnny with Mel Larch and Jason “Roadblock” Robinson outside the Empty Glass in 2010.

When I started writing PopCult and began reconnecting with my old friends, I found out that Johnny had a really rough patch of wretched health. He’d spent months in and out of hospitals with a variety of ailments, some exacerbated by his own behavior, some not. Once Mel and I went to see Johnny in Charleston Memorial. He was in ICU, and when we got there, he woke up and we talked for several minutes. I gave him a Hot Wheels Batmobile. After we left he slipped into a coma. We thought then that we’d seen our friend for the last time.

When he woke up several weeks later he thought that he’d hallucinated our visit. When I told him that we’d really come by, he then got upset because his Batmobile was missing (I got him another one). Johnny was frail at this point, but desperate to get out and be his old self again.

The problem was that years of physical sickness had done a number on Johnny’s self-esteem. He’d developed a lot of social anxiety issues, and he’d taken to medicating himself with alcohol, which at this point was terribly detrimental to his health. It was heartbreaking to watch because Johnny wanted to come out, and he’d be his old self until he hit a point where he had too much alcohol in him and his body would just shut down. At left is a photo of Johnny with Mark Beckner and me at a Nanker Phelge show in 2010 (photo by Stephen Beckner).

The problem was that years of physical sickness had done a number on Johnny’s self-esteem. He’d developed a lot of social anxiety issues, and he’d taken to medicating himself with alcohol, which at this point was terribly detrimental to his health. It was heartbreaking to watch because Johnny wanted to come out, and he’d be his old self until he hit a point where he had too much alcohol in him and his body would just shut down. At left is a photo of Johnny with Mark Beckner and me at a Nanker Phelge show in 2010 (photo by Stephen Beckner).

It wasn’t always easy being Johnny’s friend because as gregarious and charming as he could be, he was also very stubborn and did not want to follow his doctor’s advice. Some of Johnny’s friends are justifiably upset with him because, if he’d taken better care of himself, he may still be around. There’s some anger that Johnny didn’t try harder to stick around longer. It could be aggravating and frustrating caring about Johnny.

For me, I couldn’t stay mad at Johnny for long. Being a notorious non-drinker myself, I tried to get Johnny to come along to places that didn’t serve alcohol. Everybody has their demons, and Johnny’s were plentiful and robust, but you still loved the guy. He continued to spend time in and out of the hospital, but now we could keep in touch via Facebook, so he never felt totally abandoned.

And that was another of Johnny’s issues. He felt left behind by the music scene. He knew that Go Van Gogh was “this close” to breaking through (and they were). He’d develped a kind of agoraphobia coupled with a manic depressive cycle. For years he self-medicated to get enough courage to leave the house. He finally stopped drinking, but then he could only go out if he was in a manic cycle and felt up. If you couldn’t pick him up and head out right then, you’d miss the window. Dozens of times I’d be tied up when he was wanting to go out and I’d try arrange to run out with him the next day, only to have him feel too sick to go out when I got there to pick him up.

Twice earlier this year, I got lucky. Last January, just days after Lee Harrah’s mother passed away, I’d arranged to take Lee out to lunch, just to see how he was doing. That morning Johnny posted on Facebook that he wanted to go out and just do something. I messaged him immediately and asked if he wanted to join me and Lee for lunch.

The timing was finally perfect. I picked up Johnny and he was decked out head-to-toe in brand-new gear from his favorite football team, Chelsea. Johnny was a bigger anglophile than I am, to the point of watching soccer regularly. He was beaming. We were going out and he was going to help Lee. Lee was delighted to see Johnny, and helping Johnny made Lee feel better. After lunch at the China Buffet in Kanawha City we made a stop at Budget Tapes & Records. It was glorious. We all got to see our old friend John Nelson and everybody there treated Johnny like the rock star that he was born to be.

The timing was finally perfect. I picked up Johnny and he was decked out head-to-toe in brand-new gear from his favorite football team, Chelsea. Johnny was a bigger anglophile than I am, to the point of watching soccer regularly. He was beaming. We were going out and he was going to help Lee. Lee was delighted to see Johnny, and helping Johnny made Lee feel better. After lunch at the China Buffet in Kanawha City we made a stop at Budget Tapes & Records. It was glorious. We all got to see our old friend John Nelson and everybody there treated Johnny like the rock star that he was born to be.

It was a great day. I’m going to treasure that memory.

A few weeks later Johnny posted about wanting to go out again, and my day was free. This time it was just me and Johnny and we once again hit the China Buffet (he’d never been there before our first visit and loved the place), and we got to hang out and talk for about three hours.

It was the kind of rambling, hilarious conversation that you can only really have with someone you’ve known more than half your life. We joked about comparing our medical ailments like old men. We teased each other about baseball (I’m a diehard Yankees fan, while Johnny, sadly, was a Red Sox fan). We talked about film, music, the old days, and our future plans.

And we discussed mortality.

I’d mentioned how every time I write an obituary, I say it’s the last one I ever want to do. I’d “come out of retirement” to write the obituary for Lee’s mother in January, but when asked to speak at her funeral, I became the human embodiment of a deer in the headlights.

Johnny knew that I absolutely hate speaking in public. I’m fine in front of a camera or behind a microphone, but a live audience is just something I would rather never face. At my best, speaking before an audience is a hellish torment. And at a funeral, I’m at my worst.

I told him that I never wanted to write another obituary or ever speak at a funeral. Without missing a beat, Johnny replied, “Well, you won’t have to worry about that with me. I’m immortal.”

It was one of Johnny’s typical joke responses, but in a sense, he was right. His physical form may be gone, but his spirit will live on. Where ever an insecure kid in a band, totally filled with self-doubt and insecurity, puffs up and says he’s the best in the world, that’s a part of Johnny. Whenever somebody staunchly defends Charleston’s West Side, Johnny’s smiling down. Whenever somebody sarcastically punches a hole in an over-inflated ego, Johnny’s giving a thumbs up.

It was one of Johnny’s typical joke responses, but in a sense, he was right. His physical form may be gone, but his spirit will live on. Where ever an insecure kid in a band, totally filled with self-doubt and insecurity, puffs up and says he’s the best in the world, that’s a part of Johnny. Whenever somebody staunchly defends Charleston’s West Side, Johnny’s smiling down. Whenever somebody sarcastically punches a hole in an over-inflated ego, Johnny’s giving a thumbs up.

“Rock is dead they say, Long Live Rock.”

I know Johnny would probably rather have a lyric from The Jam or XTC there, but I don’t think he’d mind The Who, and it really does fit.

I’m gonna miss you, Johnny.

I’d like to think that where ever Johnny is now, he’s healthy, driving again, playing a gig with a great band every night, and has a couple of hot chicks to carry and set up his drum kit. Johnny loved being a drummer, but he hated actually carrying the damned things.

Tomorrow we’ll have more on Johnny on Radio Free Charleston, and we’ll post links to some of his video appearances here in PopCult.

Subscribe to PopCult

Subscribe to PopCult