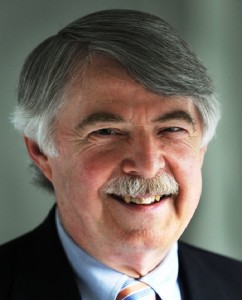

Paul Nyden: Coal reporting, making W.Va. better

August 21, 2015 by Ken Ward Jr. There’s a story I like to tell — I’m frankly not sure if it’s true — that more than a few years back a top West Virginia political leader called over to the agency that we now call the Department of Environmental Protection. This politician, an elected official, wanted the agency’s director to issue a coal-mining permit that was being held up over concerns about the damage that might be done.

There’s a story I like to tell — I’m frankly not sure if it’s true — that more than a few years back a top West Virginia political leader called over to the agency that we now call the Department of Environmental Protection. This politician, an elected official, wanted the agency’s director to issue a coal-mining permit that was being held up over concerns about the damage that might be done.

As the story goes, the agency director assured the elected official that the permit would be issued that day. But, the agency director said, “I’m going to have to put a note in our files that we issued it on your orders. You know the files I mean … the ones that Nyden looks at all the time.” The elected official, without even debating the issue, said, “Just forget it,” and hung up.

That in a nutshell is what Dr. Paul Nyden has meant to West Virginia. I’ve often told people that the greatest single piece of journalism in West Virginia history is “Who Owns West Virginia,” the remarkable project produced in 1974 by Tom Miller, then of the Huntington paper. But for my money, no one reporter’s career has lived up to former Gazette publisher Ned Chilton’s mandate for “sustained outrage” more than Dr. Nyden’s has.

As many readers probably know, we’ve been going through a difficult process here at Charleston Newspapers, as we combined the newsrooms of The Charleston Gazette and the Charleston Daily Mail into one newsroom for the new Charleston Gazette-Mail. This morning’s paper included the news that, as a part of that process, Paul is retiring.

Obviously, this is a huge loss — for the Gazette-Mail, for West Virginia, for me and others who have been mentored by Paul, and for anyone who values context and history as part of the coverage of the nation’s coal industry. But I don’t want to write about my friend here as if he’s dead or something. He’s very much full of life — and I look forward to him continuing to contribute to the public discussion about West Virginia’s past, present and future. Hopefully he’ll keep writing book reviews about foreign policy, so I won’t have to read those books myself. And there’s a project or two I have in mind I hope he and I will work on together. Maybe Paul will have more time to take in baseball games.

This is as good a time as any, though, to stop and think about Paul’s journalism, and remember his contributions and see what the rest of us can learn from them, both about how to do journalism and about what West Virginians might try to do to help move the state forward as the coal industry Paul has covered for so many years continues to decline.

For one thing, Paul’s coverage of the lax permitting and enforcement practices of the old state Department of Energy set the standard for how a local journalist can and should hold a government agency accountable. When I had been at the Gazette barely a month, I was actually assigned to write up a story documenting how the Gazette, through Nyden’s reporting, was really doing DOE’s job for it:

Division of Energy attorney George V. Piper likes to joke that Paul Nyden is the agency’s best investigator. To others, the situation isn’t very funny.

So far this year, the Gazette’s investigative reporter has uncovered more than $1 million in outstanding environmental fines and fees owed to the DOE or the federal Office of Surface Mining by coal companies. Since 1989, Nyden has revealed nearly $2 million in unpaid fines and fees … Perry D. McDaniel, a Charleston lawyer and president of the West Virginia Environmental Council, said, “”It’s a shame The Charleston Gazette has to fund the job that the coal industry should be doing and that is proper review of permit applications, especially with regard to reviewing files for violations and the proper follow-up for the imposition of civil penalties.”

My personal favorite, though, was always a piece from 1990 headlined, “Flashing blue lights reflect a boiling feud within DOE.”

William “Bolts” Willis wants to install flashing blue lights, a siren and a state police radio in a Division of Energy vehicle for his own use. Energy Commissioner Larry George has not approved the request. Willis apparently wants the lights and siren in case he has to drive to a mine disaster.

Flashing blue lights reflect a larger feud boiling up rapidly.

George and Willis, who is George’s administrative assistant, have been attacking each other privately for more than a week.

George believes Willis is trying to torpedo his recent administrative reforms. Willis apparently sees those reforms as a threat to his own turf within the agency.

Willis said Tuesday that he has no problems with George. “We have been friends too long to let anything like this happen,” he said. Willis failed to return several telephone calls on Thursday and Friday.

Behind the scenes, Willis has been lining up support for more than a week from the governor’s office. He has been calling his political allies in the United Mine Workers.

Several local UMW officials criticize Willis, but they are afraid to do so publicly. His critics say Willis has done little in his state job since he became DOE’s No. 2 man in January 1989.

Despite that, International UMW officials have apparently decided to fight hard to keep Willis at DOE. Joe Main, who heads the International UMW’s safety department, said on Thursday that International union officials would have no comment on the dispute. Main also said he did not want the dispute publicized in the media.

Environmental groups and most UMW officials in West Virginia support George. They regard him as more sensitive to environmental issues and union safety concerns than either George E. Dials or Kenneth R. Faerber, George’s two predecessors.

Of course, Dr. Nyden was writing about Don Blankenship and A.T. Massey Coal long before publications like Rolling Stone and the New York Times had heard of them. Back in 1985, he exposed a document called the “Massey Doctrine” that spelled out the company’s corporate philosophy:

A.T. Massey, founded in West Virginia in 1916, is the state’s third-largest producer. It mines 6.5 millions tons of coal a year – 70 percent of it non-union.

E. Morgan Massey, president of A.T. Massey, claims his Richmond, Va., firm is nothing but a sales broker for scores of subsidiaries and affiliates. Operating companies in West Virginia and Kentucky, says Massey, make their own business decisions.

But the “Massey Coal Company Partnership Agreement” does not portray a loose network of independent coal-mining operations.

It reveals the existence of a highly centralized corporate hierarchy controlled by an eight-member “partnership committee.”

Despite statements from E. Morgan Massey that his company is merely a sales firm, A.T. Massey’s own literature stresses the extent of company holdings at 26 mining complexes, 20 preparation plants and two new deepwater terminals in Newport News, Va., and Charleston, S. C., which can load 14.5 million tons of coal a year.

“The Massey Coal Company Doctrine,” an internal company document dated July 1982, asserts “there is little, if any, cost advantage to be gained from being a large company in the mining business.” It urges a “decentralized management design and discusses “stand alone resource units.” But Massey Coal Sales Co. and Massey Coal Export Co., the doctrine adds, will integrate sales activities of all divisions, affiliates and contractors. Decisions about the availability of capital to each operating unit are also centralized.

Work digging into Massey’s business eventually led to a landmark investigation of the abuse by the coal industry of a vast system of coal contractors that allowed major producers to avoid liabilities for environmental damage and worker safety:

Since 1978, A.T. Massey Coal Co. has created more than 110 subsidiaries and hired nearly 500 independent contractors to mine its coal. Most of the contractors eventually went out of business or bankrupt.

Former company President E. Morgan Massey believed a decentralized coal company is the most productive.

Critics say the maze of contractors helped A.T. Massey avoid paying millions of dollars in wages, health benefits, pensions, environmental cleanup costs and taxes. The maze baffled government agencies that enforce environmental laws and collect taxes.

When Blankenship sued the Gazette years later (not over a story Paul had written), the legal complaint included this paragraph:

Defendant Gazette has a long history of close relations to the UMWA and unwarranted attacks on Massey Energy and Blankenship. Gazette reporter Paul J. Nyden has had a relationship with the UMWA for decades. In 1978, Nyden — a self-described Marxist — wrote a pamphlet in which he proposed … that the energy industry be nationalized, with energy companies being taken away from private owners to be run by government. Subsequently, Nyden began to cover labor issues for Defendant Gazette and for decades has written negative articles about Massey Energy and Blankenship. Upon information and belief, Nyden has encouraged other Gazette writers to attack Massey and has conspired with the UMWA to harm Massey’s reputation.

The suit was ultimately thrown out of court. Blankenship, of course, remains in the news.

And many people involved in today’s fight against mountaintop removal may not know that Paul was among the first to write stories questioning the practice, and was involved in a battle years ago over proposals to strip mine historic Blair Mountain. He wrote many stories exposing ripoffs like the state’s Super Tax Credit program and detailing the faulty program the state used to determine property taxes for coal owners.

The stories that have always amazed me the most were stories when Paul got someone who generally probably hated the kind of journalism Paul did — and who likely disagreed with him on most political issues — to open up and tell him all sorts of secrets. A classic example was when coal operator H. Paul Kizer decided to tell Paul all about his dealings with Gov. Arch Moore. And only Paul would step in to let someone like Tony Arbaugh — a political football for people like Don Blankenship — tell his side of the story. Paul’s career has been built on giving voice to those without the power to speak up for themselves.

Obviously, I’m not exactly an objective observer on all of this. Paul’s one of my heroes. Meeting him was one of the things that taught me what journalism is supposed to be, and getting to work with and learn from him is one reason I came to the Gazette and stayed here all these years. Paul’s been a tremendous friend, and he is a great mentor to so many young reporters who come through the Gazette, often on their way to bigger things. So much of his teaching happens outside the four walls of the newsroom. He and his incredible wife, Sarah Sheets, have provided a home for many of us, feeding our stomachs and our souls.

I’m not sure what else to say about Paul Nyden and his retirement. So much of what I know about the coal industry, organized labor, and journalism I learned from him. Every time I write a story about coal, I’m standing on his shoulders. Lately, I’ve been trying in the paper and on this blog to write about what comes next for the coalfields. But it turns out, if you go back and read Paul’s dissertation, Miners for Democracy: Struggle in the Coalfields, Paul in his own way framed far better than I ever could the heart of the challenges the people of our region faced 40 years ago and are still struggling with today:

Today, thousands of railroad cars leave the mountains every day, overflowing with coal. When they return, they are empty. The people of Appalachia have nothing to say about how that coal is used nor about who reaps the harvest of riches from their mines. Someday, the vast riches of Appalachia will no longer flow into the hands of a few powerful individuals, but into the hands of the whole Appalachian and American peoples.

Subscribe to the Coal Tattoo

Subscribe to the Coal Tattoo